CHAPTER EIGHT. FOOTBALL IN 1885

I had initially intended this chapter to be an interlude. However, on reflection, I have made it a chapter as it will help you acclimatise to the period and better understand the game at the time. Hopefully I have covered all you need to know to get into football of the period (it is not all text, please scroll down for photos and graphics). This will be of benefit as we continue the story of Luton Town F.C.

Page 1 – Laws of the game

Page 2 – Rules for Umpires and Referees

Page 3 – The goalkeeper, F.A. Rules and the pitch

Page 4 – Professionalism

Page 5 – Formations and the combination game

Page 6 – Kit

Page 7 – Summary of the game

Laws of Association Football, Summer 1885

1. The limits of the ground shall be : maximum length , 200 yards; minimum length 100 yards ; maximum breadth 100 yards ; minimum breadth 50 yards. The length and breadth shall be marked off with flags and touch line; and the goals shall be upright posts, 8 yards apart, with a bar across them, 8 feet from the ground. The average circumference of the Association ball shall be not less than 27 inches, and not more than 28 inches.

2. The winners of the toss shall have the option of kick-off or choice of goals. The game shall be commenced by a place-kick from the centre of the ground in the direction of the opposite goal-line; the other side shall not approach within 10 yards of the ball until it is kicked off, nor shall any player from either side pass the centre of the ground in the direction of the opponents’ goal until the ball is kicked off.

3. Ends shall only be changed at half-time. After a goal is won, the losing side shall kick off, but after the change of ends at half-time, the ball shall be kicked off by the opposite side from that which originally did so, and always as provided in Law 2.

4. A goal shall be won when the ball has passed between the goal-posts under the bar, not being thrown, knocked on, or carried by any one of the attacking side. The ball hitting the goal or boundary posts, or goal-bar, and rebounding into play, is considered in play.

5. When the ball is in touch, a player of the opposite side to that which kicked it out, shall throw it in from the point on the boundary-line where it left the ground. The thrower facing the field of play, shall hold the ball above his head and throw it with both hands, in any direction, and it shall be in play when thrown in. The player throwing it in shall not play it until it has been played by another player.

6. When a player kicks the ball, or throws it in from touch, anyone of the same side who at such moment of kicking or throwing is nearer to the opponents’ goal-line is out of play, and may not touch the ball himself, or in any way whatever prevent any other player from doing so until the ball has been played, unless there are at such moment of kicking or throwing at least three of his opponents nearer their own goal-line; but no player is out of play in the case of a corner kick, or when the goal is kicked from the goal-line, or when it has been last played by an opponent.

7. When the ball is kicked behind the goal-line by one of the opposite side, it shall be kicked off by any one of the players behind whose goal-line it went, within 6 yards of the nearest goal-post; but if kicked behind by any one of the side whose goal-line it is, a player of the opposite side shall kick it within one yard of the nearest corner flag-post. In either case no other player shall be allowed within 6 yards of the ball until it is kicked off.

8. No player shall carry, knock on, or handle the ball under any pretence whatever, except in the case of the goal-keeper, who shall be allowed to use his hands in defence of his goal, either by knocking on or throwing, but not carrying the ball. The goal-keeper may be changed during the game, but not more than one player shall act as goal-keeper at the same time, and no second player shall step in and act during any period in which the regular goal-keeper may have vacated his position.

9. In no case shall a goal be scored from any free kick, nor shall the ball be again played by the kicker until it has been played by another player. The kick-off and corner-flag kick shall be free kicks within the meaning of this rule.

10. Neither tripping, hacking, nor jumping at a player shall be allowed, and no player shall use his hands to hold or push his adversary, or charge him from behind. a player with his back towards his opponents’ goal cannot claim the protection of this rule when charged from behind, provided in the opinion of the umpires or referee he, in that position is wilfully impeding his opponent.

11. No player shall wear any nails (excepting such as have their heads driven in flush with the leather), or iron plates, or gutta-percha on the soles or heels of his boots, or shin guards. Any player discovered infringing this rule shall be prohibited from taking further part in the game.

12. In the event of any infringement of Rules 5,6,8,9, or 10, a free-kick shall be forfeited to the opposite side, from the spot where the infringement took place.

13. In the event of an appeal for any supposed infringement of the Rules, the ball shall be in play until a decision has been given.

14. Each of the competing clubs shall be entitled to appoint an umpire, whose duties shall be to decide all disputed points when appealed to; and by mutual agreement, a referee may be chosen to decide in all cases of difference between the umpires.

15. The referee shall have power to stop the game in the event of the spectators interfering with the game.

Definition of terms

A PLACE KICK is a kick at the ball while it is on the ground, in any position in which the kicker may choose to place it.

A FREE KICK is a kick at the ball in any way the kicker pleases, when it is lying on the ground; none of the kicker’s opponents being allowed within 6 yards of the ball; but in no case can a player be forced to stand behind his own goal- line.

HACKING is kicking an adversary intentionally.

TRIPPING is throwing an adversary by the use of the legs, or by stopping in front of him.

KNOCKING-ON is when a player strikes or propels the ball with his hands or arms.

HOLDING includes the obstruction of a player by the hand or any part of the arm extended from the body.

HANDLING is understood to be playing the ball with the hand or arm.

TOUCH is that part of the field, on either side of the ground, which is beyond the line of play.

CARRYING is taking more then two steps when holding the ball.

Some important points to remember from these rules.

Barging an opponent with or without the ball was allowed.

There was no penalty kick at this time.

All free kicks, corners and kick-offs were indirect, meaning they had to touch another player before being in play.

No free kick was awarded unless an appeal was made. The “advantage” rule was not introduced until 1904 so if you appealed for a free kick, you got it. The referee had no discretion to “play on” at this time.

Opponents could stand six yards away from corners, free kicks and goal kicks.

There is no use of the word “intentional” in respect of the handball rule.

There are no goal nets.

There are no substitutes allowed during the game.

————————————————-

Page 2

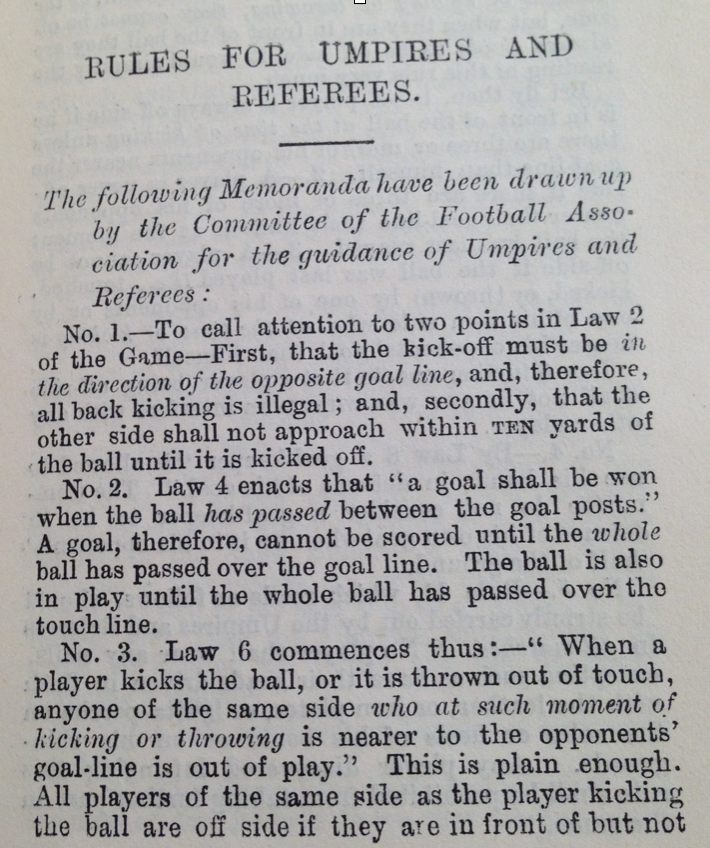

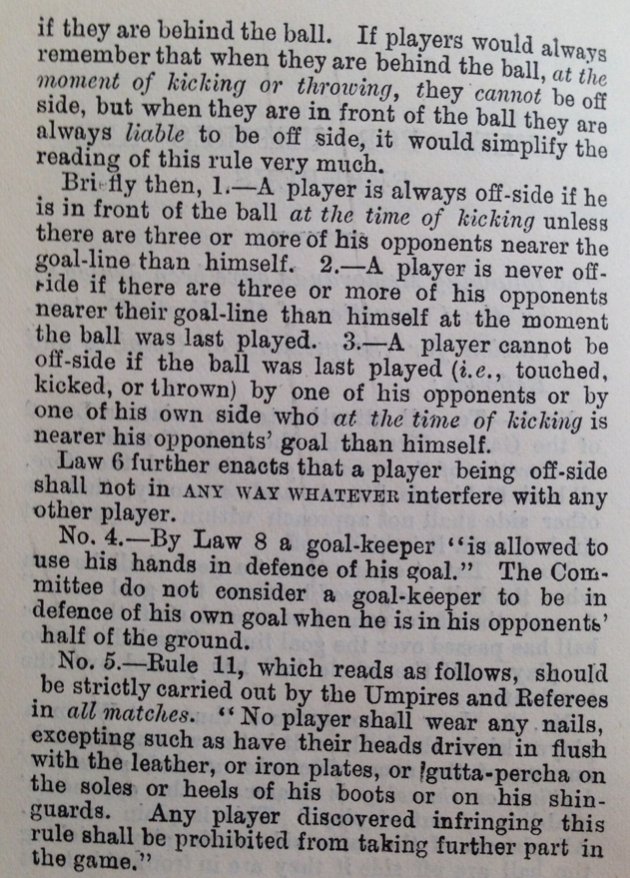

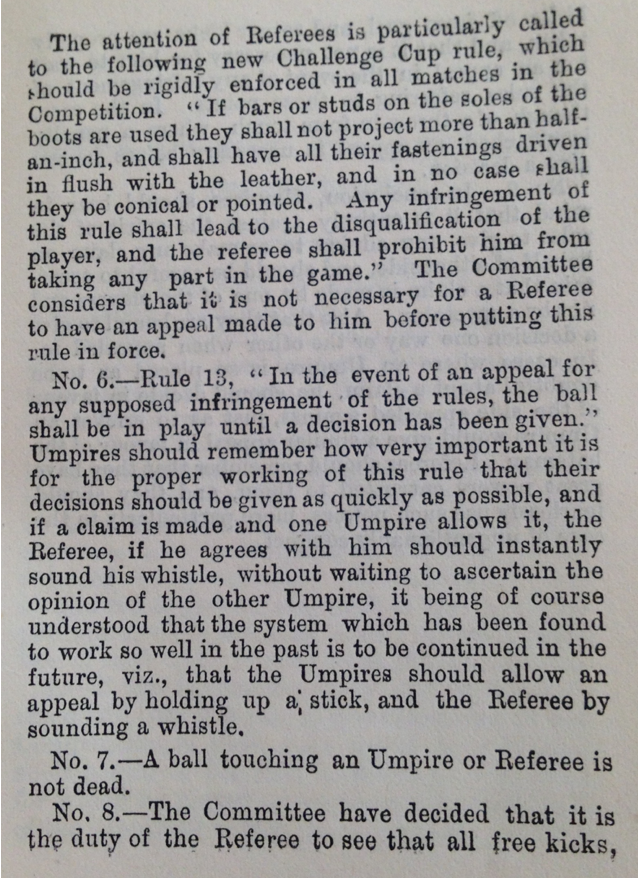

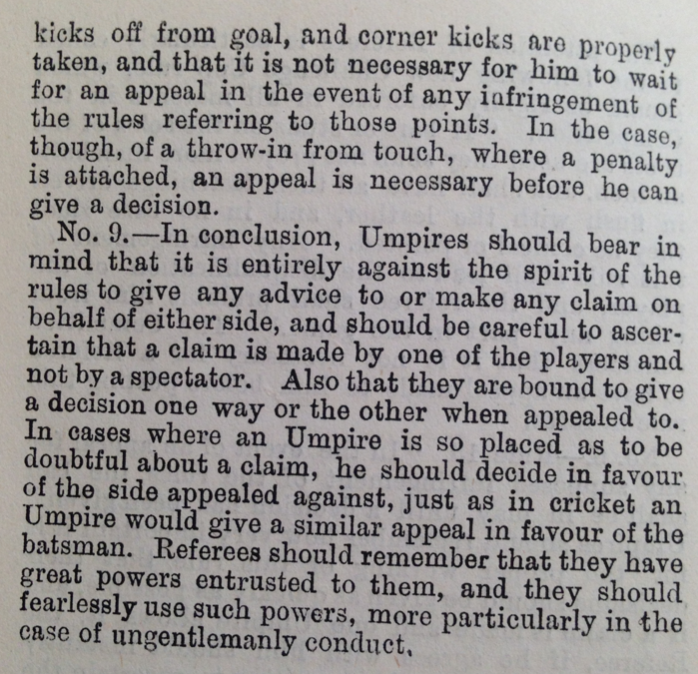

In addition, to the Laws of the game there were a set of clarification rules for umpires and referees, as set out below;

Montague Sherman, in his 1887 book “Athletics and Football” sums up the lot of the officials –

“Each side has its own umpire, who is armed with a stick or flag; the referee carries a whistle. When a claim for infringement of rules is made, if both umpires are agreed, each holds up his stick, and the referee calls the game to a halt by sounding his whistle. If one umpire allows the claim, and the referee agree with him, he calls a halt as before; if the other umpire and referee agree that the claim be disallowed, the whistle is not sounded. Two of the three officials must therefore agree in allowing the claim or the whistle is silent, and players continue the game until the whistle calls them off. Both umpires and referee, therefore, must lose no time in arriving at a decision, or so much play is wasted.”

—————————————-

Page 3

Note the clarification in respect of Law 8 about goalkeepers being able to handle the ball “in defence of his goal.” The clarification read as follows –

“The committee do not consider a goal keeper to be in defence of his own goal when he is in his opponents half of the ground”.

Potentially the goalkeeper could roam their own half and collect the ball run down the pitch and launch a kick towards their opponents goal. This sounds like a fantastic law for goalkeepers but few managed to fully take advantage of it. However, the “Carrying” clarification meant that only two steps could be taken with the ball. Bouncing the ball was required to continue running. This was difficult on uneven, muddy pitches. A more dangerous factor was that goalkeepers could be charged by opponents if they had the ball or not. This restricted many to stay on or very near their goal line with the protection of a “back” close by. This law meant that catching the ball was usually a very poor decision unless you had time to get rid of it very quickly. Punching the ball was the preferred method of saving. The law did change in 1894 whereby goalkeepers could only be charged if they had possession of the ball.

There were also “Rules of the Challenge Cup competition” issued by the Football Association which added further clarification and help with pitch markings.

Rule 27 said that “The centre of the ground shall be indicated by a suitable mark and a circle with a ten yard radius shall be marked round it, inside which no player, of the side not kicking off may stand. A line defining the six yards from the goal posts shall be marked out”.

Challenge Cup rule for pitches – near as possible to 120 yards long by 80 yards wide but not less than 110 yards long by 70 yards wide.

The above pitch markings may have been in place as early as 1874. They would not be changed until the penalty kick was introduced. More of that later.

The F.A. also issued clarification on administrative matters, for instance Challenge Cup rule 24 –

“When gate money is taken in any match played in the cup competition, the proceeds of the same, after paying ground and advertising expenses, and travelling expenses of the officials (if any) appointed by the committee, shall be divided equally between the two clubs competing in such match, except in the semi-final and final ties, when the whole of the proceeds shall be taken by the Association”.

—————————————-

Page 4

Professionalism was the number one topic of conversation in the football world at this time. The rule that had been in effect since 1882 was that:

“Any member of a club receiving remuneration or consideration of any sort above his actual expenses and any wages lost by any such player taking part in any match, shall be debarred fro taking part in either cup, inter-Association, or International contests, and any clubs employing such player shall be excluded from this Association.”

This rule had been under severe pressure and numerous protests had been lodged and adjudicated upon. It came to a head when Preston North End played Upton Park in January 1884 in the F.A. Cup. Preston were accused of professionalism which they admitted. Billy Sudell, the mastermind behind Preston’s rise said the practice was commonplace. He said;

“Professionalism must improve football because men who devote their entire attention to the game are more likely to become good players than the amateur who is worried by business cares.”

The penny eventually dropped and after much debate, professionalism was accepted later in 1885, albeit with conditions. It is a long and complicated story which I will not cover in full here. I have included a summary of events for you taken from “The Real Football” by J.A.H. Catton, 1900.

19th January 1885 F.A. – Meeting at Freemasons Tavern, London discussed professionalism. The North v Midlands and the South. Charles Crump of Birmingham and Vice-President of the Football Association led the opposition against professionalism. William Sudell of Preston North End admitted they were already professional and said that Birmingham had played men as amateurs who had been professional in Lancashire. Sham amateurism abounded he said, and added that large gates and professionalism walked hand in hand. He added that professionalism existed in Birmingham and Sheffield but he could not prove it. 113 voted for professionalism and 108 against including the South. As there was no two thirds majority the motion was not carried.

23rd March 1885 – F.A. meeting at Anderton’s Hotel saw 106 in favour and 69 against so still no two thirds majority.

20th July 1885 – F.A. meeting at Anderton’s Hotel, only 47 delegates attended, with 35 voting for and 5 against with 7 remaining neutral. Charles Crump did not protest.

Professionalism was made legal, well almost. Professionals had to be registered with the F.A.and there were strict conditions, on paper at least. The main condition was that professionals were required to either be born, or been in residence for two years, within six miles of the ground or headquarters of their club. Preston, however, was a long way from the F.A. in London and the rule was difficult to police. Professionals were also not able to play for more than one team a season without special permission of the F.A.

—————————————

Page 5

We have already covered the role of the goalkeeper in the rules affecting that position. Let us look at the rest of the team, formations, tactics and kit.

Early formations consisted of one full back, one half back and eight forwards. Due to the offside rule at the time, dribbling was the best method to get the ball forward. In theory this meant you required one back to tackle the one forward dribbling the ball. However, the forwards appeared to have played like rugby forwards and followed the ball, barging opponents out of the way for the dribbler. This caused the opposition forwards to follow the ball back towards their own goal to help out in defence. When the offside rule changed, tactics gradually changed and the number of forward was eventually reduced to five. The formations above show the decrease in forwards and by 1885 nearly every team used the 2-3-5 formation shown on the far right.

Scotland appear to have been the first team to play the 2-3-5 formation in an 1879 match against England. South of the border, however, the formation took time to find admirers. We have already seen in our story that the 2-3-5 formation reached some of the local teams, such as Chesham, much earlier than has to-date been recognised. The legend that Blackburn Olympic revolutionised the game in England by using the 2-3-5 formation in the 1883 F.A. Cup Final appears to be discredited.

The change to the 2-3-5 formation was followed by another innovation known as the “combination game.” The combination game means a passing game with players sticking to their allotted positions. Instead of individuals dribbling forward alone or in a crowd, the forwards would pass to each other by-passing defenders along the way. Usually good wing play would lead to a cross for the centre forward to hopefully score. The Cambridge University Football Club claim to have invented this form of play. What it meant was that more defenders were required, hence more backs and half-backs. Some clubs refused to adopt the combination game, others struggled to instil it into players who had grown up with a dribbling game.

But there was a more practical problem. Good combination play was only achievable if the same players practised and played together regularly. Practice was a problem for the working man. Working five and a half days a week, he would be play on a Saturday afternoon. Sunday was a day of rest. With darkness arriving early in the winter months and at 4pm during December and January, it was difficult. If players lived out of the town they played for then any practice with team mates was virtually impossible.

Absentees, through work, illness or fecklessness was also a regular problem and often teams played one short, or with a substitute from the crowd. Lord Kinnaird summed it up as early as 1879 in a letter to his old college newspaper, Home Tidings, of the Polytechnic, London. Their football team was called Hanover United.

“1 Pall Mall East, London, S.W.

Dec 31st, 1879

Sir, – I feel some reluctance in asking you to insert this communication in your next issue, as it is evident that letters sent to you are most carefully criticised by some, at least, of your readers.

I have been sorry to observe in recent accounts of the football matches the names of some of the first eleven conspicuous, not as in times past by their dashing play, but only by their absence. I know that it is hard for anyone to be present every Saturday at matches, but I think that even after making a most charitable allowance, the per centage of absentees is far too large, and ought not to continue. I feel sure it is only thoughtlessness on their part, and that every member of the football club is most anxious that the club should continue to sustain its reputation for playing a fair game, winning its matches, and turning up in good time.

I need hardly remind the club members that the only way to turn out a good eleven is to have the same team playing together, as far as possible, every Saturday. I believe the reason why so many comparatively unknown clubs, and notably some from the north, have lately come to the front is, that they thoroughly know one another’s play. I hope it is not necessary to say anything more, but i would tell the captain that my own experience is – I would far rather have an inferior man whom I could depend on turning up when wanted, than a first-rate man upon whom I could not rely.

I am sure that even your critical correspondents will not wish me to mention any names, but of they should, I shall hope to have my friend, Mr T.P., home again soon to back me up.

Yours Truly.

A.F. Kinnaird”

We need to understand the duties of the players in the 2-3-5 formation. One of the two backs, depending on the circumstances, might stick close to his own goalkeeper to prevent barging and act as a last line of defence. The other back might patrol further afield in order to break up attacks. We must also remember that the offside law calls for three defenders to be between the recipient of the ball and the goal. It therefore made sense for the second back to play higher up the pitch in order to spring the offside trap far from goal. It was a useful attribute for a back to have a big kick to get the ball away but also to launch an attack.

Half-backs were as midfielders today, taking the ball off the opposition and giving it to their own forwards and helping out in defence and attack. They were the engine room of the team.

There were outside and inside wing men who would hopefully combine to make progress down the less muddy wings and create chances for the other forwards. The centre forward would try to get on the end of a cross and generally be in the right place to score. The art of heading was not fully appreciated nor developed at this time. Having a big lad at centre forward was not a given. Pace then, as now, was a useful asset.

The players had developed many of the attributes we see today such as the long throw, the curling shot (known as the screw shot) and dribbling skills. However, other attributes, such as heading were more patchy. Some players refused to head the ball. Nevill “Nuts” Cobbold was a brilliant dribbler and played for Old Carthusians, Cambridge University and Corinthians. He played nine times for England scoring 6 goals. He refused to head the ball, and was not keen on passing either.

Montague Sherman gives us an insight;

“Upon the whole, however, spectators, while admiring the skill, can hardly help forming an opinion that this accurate heading savours more of clowning than of manly play, and many would be glad to see some sort of limit placed on the exercise”.

There were some referees did not like players jumping for a header.

————————————

Page 6

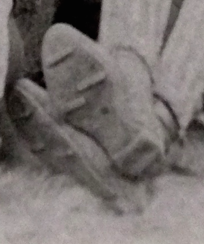

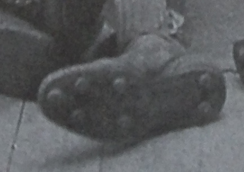

We see that Law 11 sets out the type of boots that players could wear. We are familiar with studs on the soles of football boots (below, right) but boots could also have bars as can be seen by the two photos on the left, below.

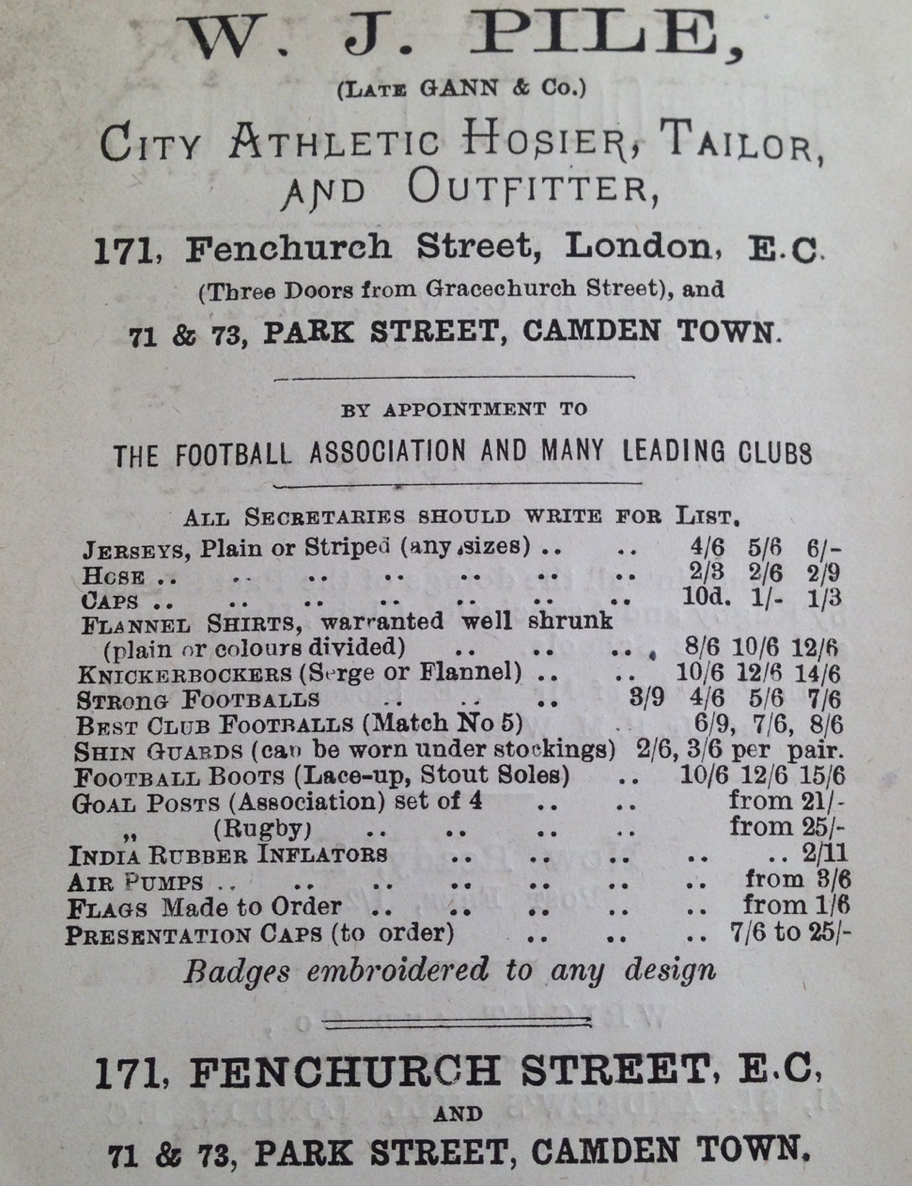

Shin guards or pads were worn outside the socks. Shin pads, boots and everything a player needed could be obtained in most towns across the country. If there was not a sports shop mail order was available or a local store could order items for you.

Adverts, such as the one below, appear in many sporting publications. Goal posts were even available. There was a badge design service offered by many companies so a unique badge for your club was possible, at a price.

For many clubs, a shirt in the clubs colours, was the only standard item amongst the 11 players. Shorts, socks and caps could be of any colour until the club was fully established and financially sound. George Deacon wears white shorts in every known photo of him in his Luton shirt. This practice continued in spite of Luton Town F.C. club rules in relation to kit colours which would come in later. George is pictured below in the cardinal shirt, with no star, which was worn between September 1889 and (around) September 1892.

Finally, all that was required was a ball. The first Law of the game set out the required circumference. The sum of 6/9 (six shillings and nine pence) would secure a ball and hours of entertainment. The price, shown left, of 9/6 was very expensive for a ball.

————————————————-

Page 7

We will learn more about all the aspects of the game as our story proceeds. To summarise, I have chosen the following by Montague Sherman from 1887;

“such is the Association game, and such are the duties of the various players, but no description can avail to convey a thoroughly accurate idea of the game as a whole. The feature of Modern Association play is essentially the combination shown by the team. While each player has his own place to keep, the field at each kick changes like a kaleidoscope, each shifting his place to help a friend or check an adversary in the new position of the game”.

1885 was the year that Bury F.C. and Millwall Rovers, later Athletic, were also formed. While Luton Town is not the oldest club, it is by no means the youngest. Dial Square, later Royal Arsenal, later Woolwich Arsenal, Plymouth Argyle and Shrewsbury Town were formed the following year. There were many late comers into the football world, such as Liverpool in 1892, West Ham in 1895 with Portsmouth F.C. and our rivals, Watford F.C. as late as 1898.

Football was in its infancy in Luton in 1885. The industrial areas of the West Midlands and the North West were leading the way. Football was fighting for credibility, not least with the press who were, in the main, hostile to the game. Without a league, clubs like Aston Villa were only getting crowds of 4 to 5,000 for their friendly matches. There would be an economic slump in 1886 and 1887 which would have a particular effect on the manufacturing areas. Many knew football had potential but the laws of the game needed tweaking to make it less brutal and more attractive. There was a need for more competitions. There was a need for a national league (the Football League did not begin until 1888). There was a need for local heroes, exciting games and victories to implant the game deep into the hearts and minds of the people.

Thank you to the following which are recommended reading;

“Goal-Post Victorian Football” volumes one and two by Paul Brown

“The Victorian Football Miscellany” by Paul Brown

“Athletics and Football” 1887 by Montague Sherman

“The Real Football” 1900 by J.A.H. Catton (Tityrus)

“The History of the Football Association” 1953, Naldrett Press

“A history of football in 100 objects” by Gavin Mortimer

cuafc.org – the website of the Cambridge University Football Club

gottfriedfuchs.blogspot.co.uk – “Before the “D” Association Football around the world, 1863-1937” – an excellent website covering the period mentioned.

The graphics were produced by Charlie Turner